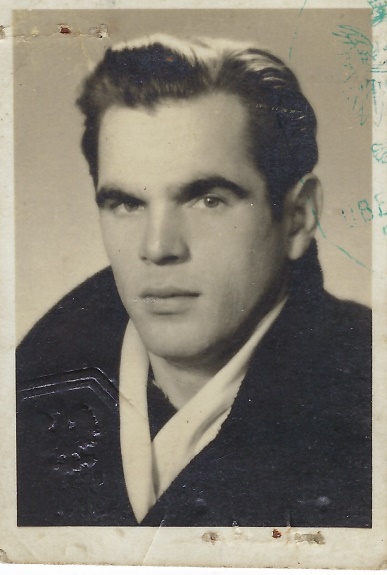

Eulogy of Teodor Jaremus

We are gathered

here today to lay to rest, Teodor Jaremus, a man whose life should be

remembered for itís toughness, for his adaptability and frugality, for his

love of life and love of his family and friends, and his concern for those

less fortunate than him.

Let me tell you a little bit about

Ted, the boy.

Teodor Jaremus was born February 5th,

1923, the second child of Polish migrant farm laborers. He was born in

Gryfice, Germany, where his father was picking potatoes. A few years

later, the family moved back to Poland and settled down in the new port city

of Gdynia. The family had a tough life. In the early years, his

parents had a boarding house on the harbor. But when the city decided

to expand the harbor, they condemned the homes in the area for business

expansion giving the Jaremusí an empty suburban lot in exchange. His

father was a political labor activist and a drinker, whose tough style and

altercations got him thrown into prison. When Tedís father came home

from working on a ship, somehow he had little to show for it. As

a child, it was rare to have meat on the table, and a pair of holey shoes

had to last for years. Tedís parents took the kids into the woods

where they would gather mushrooms to supplement their meals.

In September 1939 when WWII broke

out, Ted was 15-1/2 years old. As the Germans took control of Poland,

many Poles were recruited as ďVolk-deutschĒ, non-German conscripts that were

offered an easier way their families. Ted was one of only a few Poles

from the area that refused to fight for the Germans. He was publicly

beaten up by the Germans to humiliate him for his defiance. Most of

the Polish Volk-deutsch were sent to the Russian front lines where they were

the first to die. At this young age, Ted was shipped off as a slave

laborer, while his mother and sister were put into a concentration camp.

They lived to see another day.

Let me tell you about Ted, the young

man.

While working in the coal mines in

Verdun, France, he came up to the surface for a break and pulled a bit of

straw from the hut at the entrance to the mine, to chew on. The German

guard, thinking he was trying to shake the hut and signal the overhead US

bombers Ė drew his gun on Ted and prepared to shoot him. He pleaded in

French as best he could that he didnít know about the bombers, which he

hadnít. Somehow he went on to see another day.

Later that year, there was a partial

mine collapse and timbers fell on him breaking his collarbone and leg.

Somehow he survived another day.

Ted had a talent for

language. In the prison camp, he managed to pick up enough German and

French to become the language translator for the Germans to their Polish and

French laborers. While in the labor camp, one of his friends was being

beaten by a German officer. Ted suggested to the officer that he ďpick

on someone his own sizeĒ. While Ted wasnít exactly his size, he was a

tough young man. He beat up the officer so

bad, he knocked one eye out. Ted was put into solitary confinement for

30 days with only bread and water, from which he almost died. But

somehow he survived another day.

When the American army came through

Verdun in 1944 he joined up and served as a munitions laborer and as a cook.

He gained a great appreciation for the American soldiers who seemed to

possess an openness and strength of character that he hadnít experienced.

He took pride in cooking a good meal for the Americanís. The camp

commander publicly singled him out for his cooking efforts. This was

the beginning of his cooking career.

After the war he went back home to

Gdynia, Poland, where he obtained training in the culinary arts. He

became a cook, working on a ship from that seaport. In 1948 he took

advantage of shore leave in Galveston, Texas and ďjumped shipĒ making his

way up to Coloma, Michigan, and eventually down to Chicago, Illinois, where

he met George Gidzinski who introduced him to one of his daughters, my

mother, Eugenia. He was an illegal immigrant.

Let me tell you about Ted, the

father and provider.

While Ted was a proud Pole, a

member of St. Cyril & Methodious and later this church, and a member of the

PNA and the Polish Political League, he was also adaptable and a survivor.

He plied not only his culinary skills, but also his hard earned language

skills into becoming the head chef of several German restaurants; the

Wishing Well, the Golden Ox, and the Red Star Inn. Why did he do it?

Because at that time in Chicago, there few Polish restaurants. So he

took his skills, saw the reality of the marketplace and used them for what

they were worth for the benefit of his family. And he gave a lot in

return. He usually working 6 and sometimes 7 days a week. But he

never complained.

At Dohlís Morton House he carried

the title ďexecutive chefĒ but he was never an executive. He worked on

his feet all day long. If he wasnít working behind the broiler, he

would function as butcher to save money for the restaurant. And he

loved his work and he loved making good food. Ben and I know, because

we worked there. In 1985 when the Chicago Bears won the super bowl,

and we were talking about the game and Mike Ditka, Iíll never forget dad

saying ďIíd sure like to feed that guyĒ. He took great pleasure in

providing sustenance.

He also had a love of nature.

He loved to go walking in the woods picking mushrooms at Johnnyís house or

at the Miami woods near home. He did this because as a child, his

parents sent him to secret places in the woods to pick mushrooms so that

they would have food to eat. His life was about frugality and lack of

waste. When we were growing up, eating the food on our plate was a

rule. It was a sin not to clean your plate. You needed to eat it

all, because you never know when the enemy might be at the gate.

As

kids growing up in a suburban environment we found it hard to relate to his

strange stories from a different world. But in í62 when we came

awfully close to having a nuclear confrontation

with the Russians over missiles in Cuba, and we were being shown in school

how to hide under our desks in case of nuclear attack and there were family

conversations about building a fall out shelter, these stories of survival

and toughness all of a sudden didnít seem quite so crazy.

Ted had a big heart. From the

50ís through at least the 70ís while we didnít have much, he and mom would

send care packages back to Tedís mother and sister in communist Poland.

He opened his home to many a young Polish man trying to get his start in the

world. Mike Plewa was a good example. When Ted and I were in

Poland in 1991, we met Mikeís father who asked if there was any way his son

could come to America. Mike came and stayed with Ted off and on for 5

years. Mike was a massage therapist, and dad was glad to trade a daily

massage for room and board. Mike is now a doctor of Therapy at a

University in Poland, living a successful life. He is a life long

friend of Tedís and mine. Tedís generosity hasnít been forgotten.

As my sister said the other day,

Ted had a hard time with our Throw Away Society. It was hard coming

from a family where they barely had clothes to wear seeing people throw out

so much. As we all know, he collected a lot of stuff from the

curbside. He used some of it, sold some of it, but mostly just gave it

away to whoever could use it. It was a sin to throw things away and

not use it.

Finally, Ted was a family man.

When we were living back on Kildare, I remember many times driving to The

Edgewater Beach Hotel with dad to pick up grandpa, who didnít drive.

He worked hard to give his wife Genia a wonderful home in Morton Grove.

This wasnít something he wanted. He wanted an apartment building, a

family house back in the city. But he bowed to momís wishes.

I remember how dad would put

grandpa to work Dohlís Morton House. Grandpa was in his 70ís.

Was he taking advantage of grandpa? It sure seemed so, until I talked

with Grandpa. Grandpa appreciated the occasional work and liked to

help out. And when Grandpa came to live with mom and dad for the last

3 years of his life, it wasnít easy. Dad and mom were running their

own business, working 12-hour days, but taking care of grandpa was also a

requirement. His actions spoke louder than words.

When mom died from that terrible

Scleroderma disease, dad did everything he could to keep mom at home.

When it came time to put mom in hospital, he practically lived at the

hospital to be by her side. Watching mom suffer like that was probably

the hardest thing my dad experienced. But it was his way to do

whatever he could.

For

his children, we have many wonderful memories of our childhood. Ted

encouraged us to succeed and did his best to provide a basis for us to do

so. When we got older, he was always there to provide a meal, a bed,

some advice and a helping hand, but mostly a lot of food and a lot of

advice. As we grew up, got married and experienced our American

success, somehow he saw that he couldnít help us. We didnít need the

things he found on the curbside, although his food was always a treat.

Despite Tedís quirky ways, all of

his kids have successful marriages with families, nice homes and good jobs.

Not something that happens very often in todayís society. Iíd like to

think that some of the lessons that Ted taught us made a difference in our

lives. So let us remember Ted for his courage to live, for his

strength and perseverance in the face of hardship, and for his love for his

family and care those less fortunate than him, a life that Jesus Christ

would, I think, be proud of.

By his son, Rolfe Jaremus

Written December 24,

2005

=================================================================================

The Gavet -

Jaremus Connection

During Thanksgiving of 1990, 8

months after my mother passed away, my father Ted (his real name was Teodor)

asked me if I would write a Christmas letter to his old friend Bob Gavet. My

mother Eugenia, who was born in America and had a native grasp of English,

had been writing a yearly letter to Bob on behalf of my father, whose

writing skills were rather challenged. At that time, I had heard a little

bit about Bob Gavet and dadís wartime experience. I had occasionally read

Bob Gavetís holiday letter to Ted which dad often put on the coffee table in

the Morton Grove living room, but I really didnít know very much. So before

agreeing to do anything I asked my dad for more information.

I knew that Ted had been a slave or forced laborer working

for the Nazi war machine. As a teenager, I had heard bits and pieces of his

story but I never understood how it fit together; where he went and when

things occurred, or very much about the Gavets. Then sometime around 1986 I

interviewed my dad to nail down his wartime experiences. So hereís a little

about that Ted Jaremus - 1947 time as it relates to his Guernsey

experiences.

When the Naziís invaded Poland in September of 1939, Ted was

a 16 year old boy. His mother tried to shelter him from service but the

Naziís eventually processed all able bodied men and though they tried to

escape, Ted was eventually "enlisted". Because he was born in Grifice,

Germany while his parents were working as migrant laborers, and since he

grew up in the new Polish port city of Gdynia he and other Poles from his

hometown were offered an opportunity to fight for the Nazis as "Volk-deutch".

Out of a group of 300 Poles, he and 6 of his friends refused to join.

Although Ted was beaten and humiliated at the recruitment event, these

refuseniks were the lucky ones. They were sent off to work as slave laborers

for the German war machine. Those Poles that agreed to fight for the Germans

were sent to the German-Russian front line and were never seen again.

Tedís first assignment was working as a laborer on a nearby

Prussian farm. There he developed a reputation for being a hard worker.

Sometime around 1942 he was send by train through Germany to occupied France

and then shipped over to Guernsey, one of the English Channel Islands off

the coast of France. The British had evacuated the island as they had

decided early in the war not to defend the islands. Most of the citizens

were relocated to northern English towns, however a number of Guernsians,

refused to leave.

After the Naziís took over the Island, they decided to build

sea side concrete bunkers and an extensive series of underground tunnels.

They built these as underground supply depots and fortifications for what

they erroneously believed was a coming British invasion. Ted was one of many

Polish slave laborers and other skilled Axis craftsmen from the continent

that worked on this project. For the skilled Axis workers, this was a job

assignment and they were paid and treated like employees. For the slave

laborers, the reality was quite different. As my father explained, the

conditions were very harsh for the Poles (and other nationalities) and the

work was very hard. The granite rock that they were mining into was very

hard. Some days they only made a few inches of tunneling progress. Later the

Germans shipped over some diamond tipped grinding machines that allowed them

to make much better progress. The Poles, like Ted, were largely there to

remove the stone debris and do the back breaking manual labor work in the

tunnels. The conditions were harsh for the laborers. The food was basic and

of poor nutrition. Ted said he was constantly hungry. Many Poles died during

the work efforts.

While going to work from the barracks, Ted walked along the

back side of a local farm where Ted slowly befriended a local farm boy Bob

Gavet. Ted didnít know English and Bob didnít know Polish but somehow they

managed to communicate. Bobís mother took a liking to Ted as he was a

slight, young, polite man. She gave him some milk or food if they had some

to spare. Ted explained that his motivation was to get a fallen apple from

their apple tree, a piece of bread, or something else to eat as the rations

for the laborers was very meager. Bob and Bobís mother stuck their necks out

for him and helped him survive those difficult days.

So back to Thanksgiving, 1990. With little knowledge about

the writing arrangements and a little knowledge about the Guernsey/Gavet

story, I said, "what do you want me to write?". I was thinking maybe dad

would dictate the contents of a letter and I would write for him. That

wasnít to be the case. Rather, my dad said, "tell Bob whatís going on with

us". He gave me a letter that he had gotten from Bob. We talked a bit about

it, but I made no commitment. I was busy with work as I had recently started

a new job, so the letter writing effort languished for a while. When we got

together for Christmas later that year, dad asked again if I would write. So

after giving it a bit of thought, and asking him what he wanted me to say, I

wrote the first letter. I wrote it in Tedís voice so to say, explaining what

happened to his wife and other things that had happened during the year. The

extended Jaremus family at the time all had young children, so there was a

lot of family stuff to write about. That was the beginning of my

correspondence with Bob.

The following year dad got another letter from Bob. He had

read it and he gave it to me, and once again asked me to write to Bob for

him. I once again asked him what he wanted to say. He gave me a few thoughts

and his encouragement : "Just tell him whatís going on with the family". So

I was getting the idea about how this was going to work. I went ahead and

wrote another letter. As time went on, I took ownership of the writing duty.

I was beginning to find it interesting to correspond with Bob. He was a

good, gracious person that wrote in the British vernacular. He talked about

the old family farm, his brother who was still lived on the farm. Bob was

retired by then. He talked about his wife Marjorie, their grown children and

grandchildren.

As I came to understand, life on Guernsey after the war had

changed quite a bit. For a few decades after the war, Guernsey was still an

agrarian island. Most of the people were subsistence farmers, living quiet

unassuming lives away from the hustle and bustle of the British cities.

During the 70ís and 80ís, Guernsey became a hot house island growing

tomatoes, lettuce, peppers and other warm weather vegetables and flowers

that didnít grow so well in England proper. While working for a local

garage, Bob invested and had built several hot houses and grew tomatoes and

flowers for export. But as time went on, European trade and transportation

methods improved, and when the oil embargo of 1974 hit with the soaring oil

prices, transportation costs increased dramatically. These kinds of

vegetables could be grown more easily in Holland or Italy and Spain and

transported by ship to England less expensively than from Guernsey where the

cool oceanic climate required greenhouse growing.

Then sometime in the 70ís or 80ís, the Channel Islands,

while part of the United Kingdom, but having independence from Britain Ė

became an off-shore banking destination. British people could park some of

their money in Guernsey or Jersey (a sister island) banks and not have to

pay the high taxes that were being charged in mainland England. As a result,

a large number of banks and financial institutions set up shop on the

island. Guernsey and Jersey became off shore financial centers. One of Bob

and Marjorieís daughters worked at one of these banks. But the key thing was

that the island economy changed from being a self- sustaining largely

agricultural quiet outpost known for itís Jersey cows, their cheese and

butter to becoming a tony financial haven. With the coming of more banks and

wealthy bankers, a new marina was built in the 80ís. Local hotels were

refurbished and built. The picturesque fishing town of St. Peters Port

became a desirable tourist destination.